Exercise doesn't just benefit your body, it also strengthens your brain

Growing up in the Netherlands, Henriette van Praag had always been active, playing sports and riding her bike to school every day. Then, in the late-1990s, while working as a staff scientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, she discovered that exercise can spur the growth of new brain cells in mature mice. After that, her approach to exercise changed.

“I started to take it more seriously,” says van Praag, now an associate professor of biomedical science at Florida Atlantic University. Today, that involves doing CrossFit and running five or six miles several days a week.

Whether exercise can cause new neurons to grow in adult humans – a feat previously thought impossible, and a tantalising prospect to treat neurodegenerative diseases – is still up for debate. But even if it’s not possible, physical activity is excellent for your brain, improving mood and cognition through “a plethora” of cellular changes, van Praag says.

What are some of the benefits, specifically?

Exercise offers short-term boosts in cognition. Studies show that immediately after a bout of physical activity, people perform better on tests of working memory and other executive functions. This may be in part because movement increases the release of neurotransmitters in the brain, most notably epinephrine and norepinephrine.

“These kinds of molecules are needed for paying attention to information,” says Marc Roig, an associate professor in the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University. Attention is essential for working memory and executive functioning, he adds.

The neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin are also released with exercise, which is thought to be a main reason people often feel so good after going for a run or a long bike ride.

The brain benefits really start to emerge, though, when we work out consistently over time. Studies show that people who work out several times a week have higher cognitive test scores, on average, than people who are more sedentary. Other research has found that a person’s cognition tends to improve after participating in a new aerobic exercise program for several months.

Roig adds the caveat that the effects on cognition aren’t huge, and not everyone improves to the same degree. “You cannot acquire a super memory just because you exercised,” he says.

Physical activity also benefits mood. People who work out regularly report having better mental health than people who are sedentary. And exercise programs can be effective at treating people’s depression, leading some psychiatrists and therapists to prescribe physical activity.

Perhaps most remarkable, exercise offers protection against neurodegenerative diseases. “Physical activity is one of the health behaviors that’s shown to be the most beneficial for cognitive function and reducing risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia,” says Michelle Voss, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Iowa.

How does exercise do all that?

It starts with the muscles. When we work out, they release molecules that travel through the blood up to the brain. Some, like a hormone called irisin, have “neuroprotective” qualities and have been shown to be linked to the cognitive health benefits of exercise, says Christiane Wrann, an associate professor of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School who studies irisin. (Wrann is also a consultant for a pharmaceutical company, Aevum Therapeutics, hoping to harness irisin’s effects into a drug.)

Good blood flow is essential to obtain the benefits of physical activity. And conveniently, exercise improves circulation and stimulates the growth of new blood vessels in the brain. “It’s not just that there’s increased blood flow,” Voss says. “It’s that there’s a greater chance, then, for signalling molecules that are coming from the muscle to get delivered to the brain.”

Once these signals are in the brain, other chemicals are released locally. The star of the show is a hormone called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, that is essential for neuron health and creating new connections – called synapses – between neurons. “It’s like a fertiliser for brain cells to recover from damage,” Voss says. “And also for synapses on nerve cells to connect with each other and sustain those connections.”

A greater number of blood vessels and connections between neurons can actually increase the size of different brain areas. This effect is especially noticeable in older adults because it can offset the loss of brain volume that happens with age. The hippocampus, an area important for memory and mood, is particularly affected. “We know that it shrinks with age,” Roig says. “And we know that if we exercise regularly, we can prevent this decline.”

Exercise’s effect on the hippocampus may be one way it helps protect against Alzheimer’s disease, which is associated with significant changes to that part of the brain. The same goes for depression; the hippocampus is smaller in people who are depressed, and effective treatments for depression, including medications and exercise, increase the size of the region.

What kind of exercise is best for your brain?

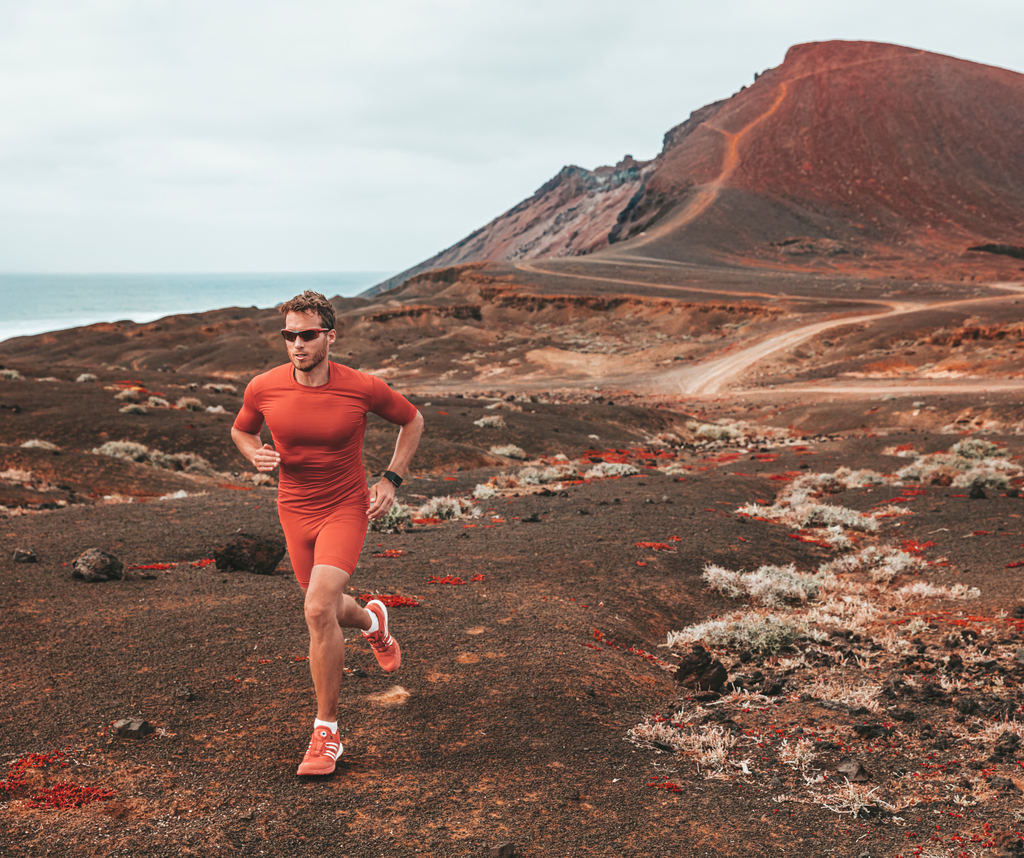

The experts emphasise that any exercise is good, and the type of activity doesn’t seem to matter, though most of the research has involved aerobic exercise. But, they add, higher-intensity workouts do appear to confer a bigger benefit for the brain.

Improving your overall cardiovascular fitness level also appears to be key. “It’s dose-dependent,” Wrann says. “The more you can improve your cardiorespiratory fitness, the better the benefits are.”

Like van Praag, Voss has incorporated her research into her life, making a concerted effort to engage in higher intensity exercise. For example, on busy days when she can’t fit in a full workout, she’ll seek out hills to bike up on her commute to work. “Even if it’s a little,” she says, “it’s still better than nothing.”

Leave a comment